There are more than 3,000 written languages, and business and our lives are increasingly global. Even if your organization doesn’t touch even half of them (really, kudos if you do!), it’s hardly an uncommon need to be able to organize your data or communicate concepts or entities across multiple languages. This might include products that need to be sold across multilingual experiences, websites that need to be navigated across languages, retrieving search results not in your native language, or collaborating in a multilingual repository.

Fortunately, if you’re well-grounded in how to manage taxonomies and ontologies in one language, you’re well equipped to expand into multiple languages.

So – what’s necessary to equip your data for success in this multilingual world?

Things Not Strings

Ensure that you’re using a UUID-centered approach, so that you’re translating concepts or entities, not strings and terms. This means that the languaged label – whatever your preferred language – is merely an attribute of that concept – and all languaged labels are equivalent (rather than having to pick one languaged string as the “real” name, and the others merely as translations). This is just as true for other languaged fields (synonyms, notes, other text attributes) as the primary name.

All Systems Go

Ensure that whatever system or framework you’re using handles multilingual (though most systems worth their salt should.) Specifically, determine which languages you’ll need, and think about logic and hierarchy among language families (e.g. you’ll be able to use the same labels for Portuguese and Brazilian Portuguese nearly all the time – but may need different ones in some cases; do you want to duplicate for all entries, or can you set a fallback logic?). Also ensure you have a method to handle any unlanguaged data you may be using (mostly entities). Make sure to vet character encoding and sets and that they cover all characters you need.

Best Practices Make Perfect

Good information design and adherence to standards and best practices will help you throughout this. A well-designed, disambiguated information structure will be easier to express across languages (e.g., adhering to ISO 25964 and Z39.19) and easier to adjust for compromises. For example, terms that aggregate multiple concepts (naughty!) can be unusually messy to translate; or if you need to adjust categories, starting with roughly balanced, even depth of granularity will make resorting easier.

Start With the End in Mind

This is perhaps first, before all other preparation: Understand your organization’s needs for multilingual, and what you need to design for. Why are you doing this, and what are the goals? What’s the domain and the data and content you’re working with?

Is this primarily about bringing together content across languages (e.g., search in your native language, get all results; everyone uses the same medical code across languages, etc.)? Or are distinctions important there (I need to handle royalties for this portrayal and only want the Bulgarian instances)?

Perhaps most crucially – Are the concepts and entities the same across languages and localities? Entities are more likely to be the same across languages (a country might be called differently but is the same thing); concepts are more likely to present some challenges there. Taxonomies and other knowledge structure reflect how people think, which varies by culture, reflected by language.

One Taxonomy or Many? Symmetric or Asymmetric?

So, there are several legitimate ways of approaching the structure of your data – but your choice should flow naturally from the last set of points (along with some pragmatic implementation concerns).

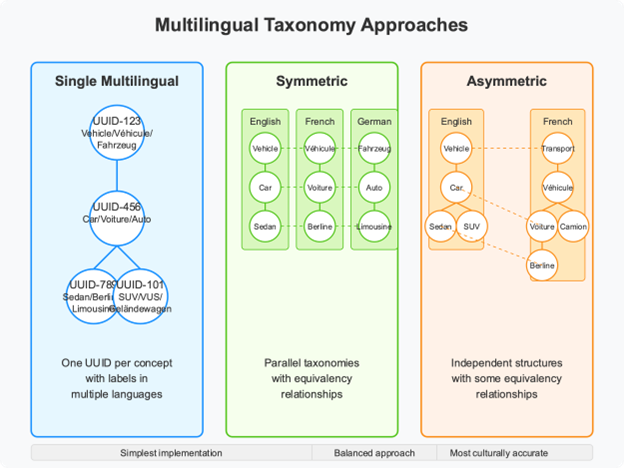

Single Multilingual Taxonomy

This uses a single taxonomy, where all covered languages are tethered on a single term.

- Pros – This is the simplest to manage and implement in nearly all cases, and the most fully unified, where each concept has a single root identifier across languages.

- Cons – If there are cases where the concepts vary across languages, this is difficult to consolidate into a single taxonomy. While it can be possible to carefully compromise, in some cases, one language “wins” – and this can end up feeling awkward or confusing for users in other languages. It does also assume that consuming systems can handle the multilingual logic and present the desired language as appropriate.

Symmetric Taxonomies

This has multiple taxonomies, one per language, designed in perfect parallel to each other, with equivalency relationships tethering them.

- Pros – This lets you distinguish between concepts as expressed per language, while having a clear equivalency between them. This is the middle road in terms of maintenance and effort; you’re essentially managing only one taxonomy, but mapping it expressed across languages. This approach gives you slightly more flexibility for cross-language concept variance, though this is limited by the need for concept-by-concept equivalencies.

- Cons – This is more work than the single taxonomy, since there’s one per language, and you’re maintaining equivalency relationships across them. Symmetric taxonomies are often more complex for consuming systems, because they need to consume multiple parallel taxonomies and understand how they relate to each other.

Asymmetric Taxonomies

This implementation uses one taxonomy per language, wholly independent and often significantly different per languages., with equivalency relationships where appropriate

- Pros – Bespoke per language and locality, this may most fully reflect the best structure and experience for each language.

- Cons – If your aim is to consolidate across languages, this approach is the least effective at doing so. This is also the most resource intensive to maintain.

Born Multilingual or Branching Out from Your Taxonomy’s Native Tongue?

Ideally – your taxonomy would grow up speaking all the languages it needs. There are benefits here – you understand the intended scope, design for it, adjusting so that the organization and concepts work for all languages.

Starting in one language and then needing to expand coverage for other languages is likely often the most common scenario.

The major challenge, as we’ve discussed above, is there isn’t always a one-to-one relationship between concepts across languages, and without adjustments as you go, you can end up with a taxonomy that’s technically translated but not localized – it doesn’t reflect the categories that native speakers of that language use. Ideally, if you’re doing this, you should have a good change management process in place and be willing to work through adjusting the existing data so it can compromise on concepts that make sense in all languages.

Do be sure when translating that you aren’t translating terms but rather concepts.

In a previous project, I used linked open data equivalencies such as Wikidata and Geonames (you’re maintaining those linked data equivilencies, right?) to find concept-level equivalencies per language, including synonyms and alternate labels (or identify gaps – there isn’t always a good equivalency!), and then had humans fluent in those languages review for goodness and brand fit of preferred label choices; this was an efficient and effective way to rapidly expand across languages.

Conclusion

In our increasingly connected global ecosystem, multilingual taxonomies and ontologies serve as essential bridges across the world’s linguistic landscape. Whether you choose a single unified taxonomy, symmetric parallel structures, or asymmetric language-specific approaches, success depends on thoughtful planning and implementation. By focusing on concepts rather than strings, ensuring your systems can handle multiple languages, adhering to information design best practices, and clearly defining your organizational needs, you’ll be well-positioned to create knowledge structures that transcend linguistic boundaries. The journey may require compromises and careful attention to cultural nuances, but the reward is a robust framework that enables seamless information sharing, discovery, and collaboration across languages. As organizations continue to expand globally, these multilingual foundations will become not just valuable assets but necessary infrastructure for connecting our modern Tower of Babel.